地铁车站

庞德

人流中这几张脸魔幻般浮现;

雨湿蒙蒙花瓣偎在乌黑树干。

原文:

In a Station of the Metro

by Ezra Pound

The apparition of these faces in the crowd;

Petals on a wet, black bough.

背景资料《关于庞德的一首小诗的讨论》):

一、这是庞德(Pound)的一首意象诗(imagist poem). 除了标题,全诗仅两句。第一意象是apparition,把突然看见的美丽面孔喻作梦境一般,奇妙而神密。第二意象是petals, 这个词使一张张可爱的脸有了具体的形象,更富魅力。

二、IMAGISTS:A group of English and American poets (c.1909—1917) who rebelled against the exuberance and sentimentality of 19th-cent. verse. Influenced by CLASSICISM, Chinese and Japanese poetry, and the French SYMBOLISTS, they advocated a hard, clear, concentrated poetry, free of artificialities and replete with specific physical analogies. The group included Ezra POUND, Richard ALDINGTON, Amy LOWELL, and Hilda DOOLITTLE.

三、1.这首诗据Pound自己记载,是一个下雨的晚上,他走出巴黎的一个地铁站,突然看到许多女人和儿童漂亮的脸庞,不知如何表达内心的感受,后来却发现可以用色彩表达感情。开始他写了30行,不满意,半年后改为15行,又过了一年终于成了这首类似于日本俳句的2行诗。

2. 后句是前句的比喻,两行并列不用关联词,这在中国古诗中也常见,如:嘈嘈切切错杂弹,大珠小珠落玉盘。

又如:玉容寂寞泪阑干,梨花一枝春带雨

四、其它的翻译展列如下,见仁见智,各取所好——

1. ataloss (译) 《地铁车站》

人群中突现幻影,一张张俊脸,

湿漉漉,黑枝丫上一片片花瓣。

2.罗池(译)在地铁站

人潮中这些面容的忽现;

湿巴巴的黑树丫上的花瓣。

3.钟鲲(译)地下车站

人群中幻影般浮现的脸

潮湿的,黑色树枝上的花瓣

4.成婴(译)地铁车站

人群中这些脸庞的幻影;

潮湿又黑的树枝上的花瓣.

5.李德武(译)在伦敦的地铁车站里

这些脸的幻影在人群中,

一条潮湿的、黑色枝干上的点点花瓣。

6.赵毅衡(译)地铁车站

人群中这些面庞的闪现;

湿漉的黑树干上的花瓣。

7.飞白(译)在地铁车站

这几张脸在人群中幻景般闪现;

湿漉漉的黑树枝上花瓣数点。

8.裘小龙(译)地铁车站

人群里忽隐忽现的张张面庞,

黝黑沾湿枝头的点点花瓣。

又:人群中这些脸庞的隐现;

湿漉漉、黑黝黝的树枝上的花瓣。

9.杜运燮(译)在一个地铁车站

人群中这些面孔幽灵一般显现;

湿漉漉的黑色枝条上的许多花瓣。

又:人群中这些面孔幽灵般显现;

湿漉漉的黑枝条上朵朵花瓣。

10.张子清(译)地铁站里

出现在人群里这一张张面孔;

湿的黑树枝上的一片片花瓣。

11.江枫(译)在一个地铁车站

这些面孔似幻象在人群中显现;

一串花瓣在潮湿的黑色枝干上。

12.郑敏(译) 地铁站上

这些面庞从人群中涌现

湿漉漉的黑树干上花瓣朵朵

俳句

俳句是日本人所喜闻乐见的文学形式之一,它含蓄,富有韵味,诗形短小,歌咏自然与人,在日本文学史上独放异彩。它既表现了日本人民岛国风情的生活情节,也反映了日本民族的独特的审美意识和美学观念。日本诗歌在承袭中国古典诗歌传统的同时,有其偏狭而独特的发展:题材更狭窄,形式更凝炼,审美更纤细。俳句是日本传统诗歌形式中形体最小的一种。一首俳句只有十七个音,句调为五、七、五。在中国古典诗歌中,词体最短的是"竹枝",单调的每首二句十四字;其次是"归字谣",每首十六字。诗体最短的是五言绝句

The Red Wheelbarrow

William Carlos Williams

So much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens

这么多

全靠

一辆红轮子的

手推车

因为雨水

而闪光

旁边是一群

白色的小鸡。

Fog

Carl Sandburg

The fog comes

On little cat feet.

It sits looking

Over harbor and city

On silent haunches

And then moves on.

雾踏着

小猫脚步而来.

静静蹲坐

细细俯视

海港和城市

然后再起行.

禅诗

白鹭立雪,愚人见鹭,

聪者观雪,智者见白。

--林清玄

New Criticism-1

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

New Criticism was a dominant trend in English and American literary criticism of the mid twentieth century, from the 1920s to the early 1960s. Its adherents were emphatic in their advocacy of close reading and attention to texts themselves, and their rejection of criticism based on extra-textual sources, especially biography.

Key concepts

The notion of ambiguity is an important concept within New Criticism; several prominent New Critics have been enamored above all else with the way that a text can display multiple simultaneous meanings. In the 1930s, I. A. Richards borrowed Sigmund Freud's term "overdetermination" (which Louis Althusser would later revive in Marxist political theory) to refer to the multiple meanings which he believed were always simultaneously present in language. To Richards, claiming that a work has "One And Only One True Meaning" is an act of superstition (The Philosophy of Rhetoric, 39).

In 1954, William K. Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley published an essay entitled "The intentional fallacy", in which they argued strongly against any discussion of an author's intention, or "intended meaning." For Wimsatt and Beardsley, the words on the page were all that mattered; importation of meanings from outside the text was quite irrelevant, and potentially distracting. This became a central tenet of the second generation of New Criticism.

On the other side of the page, so to speak, Wimsatt proposed an "affective fallacy", discounting the reader's peculiar reaction (or violence of reaction) as a valid measure of a text ("what it is" vs. "what it does"). This has wide-ranging implications, going back to the catharsis and cathexis of the Ancient Greeks, but also serves to exclude trivial but deeply affective advertisements and propaganda from the artistic canon.

Taken together, these fallacies might compel one to refer to a text and its functioning as an autonomous entity, intimate with but independent of both author and reader. This reflects the earlier attitude of Russian formalism and its attempt to describe poetry in mechanistic and then organic terms. (Both schools of thought might be said to anticipate the 21st century interest in electronic artificial intelligence, and perhaps lead researchers in that field to underestimate the difficulty of that undertaking.)

Studying a passage of prose or poetry in New Critical style requires careful, exacting scrutiny of the passage itself. Formal elements such as rhyme, meter, setting, characterization, and plot were used to identify the theme of the text. In addition to the theme, the New Critics also looked for paradox, ambiguity, irony, and tension to help establish the single best interpretation of the text. Such an approach may be criticized as constituting a conservative attempt to isolate the text as a solid, immutable entity, shielded from any external influences such as those of race, class, and gender. On the other hand, the New Critical emphasis on irony and the search for contradiction and tension in language so central to New Criticism may suggest the politics of suspicion and mistrust of authority, one that persisted throughout the cold war years within New Criticism's popularity. The Southern Agrarians, for instance, enfolded New Criticism's emphasis on irony into their anti-authoritarianism and criticism of the emerging culture of spending, consumption, and progress but — in the view of such writers as Robert Penn Warren — authoritarian populism early in the 20th century. Perhaps because of its usefulness as an unassuming but concise tool of political critique, New Criticism persisted through the Cold War years and immanent reading or close reading is now a fundamental tool of literary criticism, even underpinning poststructuralism with its associated radical criticisms of political culture. New Critical reading places great emphasis on the particular over the general, paying close attention to individual words, syntax, and the order in which sentences and ideas unfold as they are read. They look at, for example, imagery, metaphor, rhythm, meter, etc.

Frost said in 1931, “I started calling myself a synecdochist when others called themselves Imagists or Vorticists…A little thing touches a larger thing.”

(言近意远,因微见著)

Synecdoche(提喻)---a figure of

speech in which a part of an object is used to represent the whole object or

idea. 提喻是一种以部分代全体,单个代类别,具体代抽象(反之亦然)的辞格。

1. We had dinner at dollars a head.

2. The bus conked out.

metonymy(借代)

a figure of speech in which the name

of some objects or idea is substituted for

another name to which it has some relation. 用一事物的名称来代替与之有关联的另一事物。

1.Let’s drink a cup or two.

2.They were short of hands.

3.The kettle is boiling.

4.My TV is out of order.

5.The pen is mightier than the sword.

6.He could hardly earn his everyday bread.

摘罢苹果

长梯穿过树顶,竖起两个尖端

刺向沉静的天穹。

梯子脚下,有一只木桶,

我还没给装满,也许

还有两三个苹果留在枝头

我还没摘下。不过这会儿,

我算是把摘苹果这活干完了。

夜晚在散发着冬眠的气息

——那扑鼻的苹果香;

我是在打磕睡啦。

我揉揉眼睛,

却揉不掉眼前的奇怪——

这怪景像来自今天早晨,

我从饮水槽里揭起一层冰——

像一块窗玻璃,隔窗望向

一个草枯霜重的世界。

冰溶了,我由它掉下,碎掉。

可是它还没落地,我早就

膘膘肪脆,快掉进了睡乡。

我还说得出,我的梦

会是怎么样一个形状。

膨胀得好大的苹果,忽隐忽现,

一头是梗枝,一头是花儿,

红褐色的斑点,全看得清。

好酸疼哪我的脚底板,

可还得使劲吃住梯子档的分量,

我感到那梯子

随着弯倒的树枝,在摇晃。

耳边只听得不断的隆隆声——

一桶又一捅苹果往地窖里送。

摘这么些苹果,

尽够我受了;我本是盼望

来个大丰收,可这会儿已累坏了,

有千千万万的苹果你得去碰,

得轻轻地去拿,轻轻地去放.

不能往地上掉。只要一掉地,

即使没碰伤,也没叫草梗扎破,

只好全都堆在一边,去做苹果酒,

算是不值一钱。

你看吧,打扰我睡一觉的是什么,

且不提这算不算睡一觉。

如果土拨鼠没有走开,

听我讲睡梦怎样来到我身边,

那它就可以说,

这跟它的冬眠倒有些像,

或者说,这不过是人类的冬眠。

译者:方平

摘罢苹果

我的长梯子还搭在一棵树上

梯顶的两端插向天空,

梯子旁边,有一个桶

我还没装满,树枝上

可能有两三个苹果还没摘

但摘苹果的活计现在已结束。

冬夜里的睡眠将是美妙的,

那苹果的香气:我在打瞌睡了。

我的眼前,总抹不去那奇异的

我透过一块玻璃看到的情景——

早上时我从水槽里捞起一层冰

我对着它看这草色灰暗的世界。

它开始融化,我任它掉下去摔碎。

而在它掉落之前

我差不多已经睡着了,

我还能说得出

我刚开始做梦时的情形。

隐隐约约见好大的苹果,

有叶梗和花柄,

每一个褐色的斑点都看得很清。

我的脚心已疼痛难忍

却还是用力踩圆形的梯蹬。

我感到梯子随倾斜的树枝摇晃。

不断听到地窖里

隆隆的声响,

苹果一桶一桶往窖里送。

因为摘了太多的苹果,

面对原本盼望的丰收

我已疲惫不堪。

有成千上万的苹果得用手去摸,

得小心地拿起,放下,不能让掉落。

而所有

砸在地上的苹果,

不管是否碰伤或是被草梗扎破,

都得扔到造苹果酒的堆里

因为没有价值。

我的这一觉,可见有多麻烦,

且不说睡得如何。

要是土拨鼠还没消失,

在我描述其进展的当儿,他可能会说

那是否有点像他的冬眠,

或者只是有些人的睡眠。

李晖 译

赏析:

This poem is so vivid a memory of experience on the farm in which the end of labor leaves the speaker with a sense of completion and fulfillment yet finds him blocked from success by winter's approach and physical weariness.

雪夜林边小立

我想我认识树林的主人

他家住在林边的农村;

他不会看见我暂停此地,

欣赏他披上雪装的树林。

我的小马准抱着个疑团:

干嘛停在这儿,不见人烟,

在一年中最黑的晚上,

停在树林和冰湖之间。

它摇了摇颈上的铃铎,

想问问主人有没有弄错。

除此之外唯一的声音

是风飘绒雪轻轻拂过。

树林真可爱,既深又黑,

但我有许多诺言不能违背,

还要赶多少路才能安睡,

还要赶多少路才能安睡。

译者:飞白

未选择的路

黄色的树林里分出两条路,

可惜我不能同时去涉足,

我在那路口久久伫立,

我向着一条路极目望去,

直到它消失在丛林深处。

但我却选了另外一条路,

它荒草萋萋,十分幽寂,

显得更诱人,更美丽;

虽然在这两条小路上,

都很少留下旅人的足迹;

虽然那天清晨落叶满地,

两条路都未经脚印污染。

呵,留下一条路等改日再见!

但我知道路径延绵无尽头,

恐怕我难以再回返。

也许多少年后在某个地方,

我将轻声叹息把往事回顾:

一片树林里分出两条路,

而我选了人迹更少的那一条,

从此决定了我一生的道路。

译者:顾子欣

•�������� 未择之路 (又名:没有走过的路)

•�������� •�������� 漫步泛黄森林 有两条路岔口前方

只能选择 两条路中的一条

一介过客 我竟驻足良久。

眼向一条路 竭尽全力四望

树丛蜿蜒 我看不到尽头

•�������� •�������� 我心没有波澜 径直走向另外一条

这一条路 会更接近我的归宿吗?

绿草茵茵 植被深深。

一段旅程后 我才发觉

所遭遇景象 与未择之路几近相同!

•�������� •�������� 晨光均匀倾洒在 这两条路上

落叶期待那来 自远方的脚步声

哦我何时才能走过那一条未择之路呢?

我似乎明白一条路 终会与另一条路相逢

又感迷茫 是否我还能再回到从前

•�������� •�������� 也许多年以后 在某个场合

回忆往昔 我会为之感叹----

在森林中 当面对两条路之岔口时

我选择了 少有人迹的那一条

一切的差别 就从那一刻开始!

The old dog barks backward without getting up,

I can remember when he was a pup.

The Pasture

I’m going out to clean the pasture spring;

I’ll only stop to rake the leaves away

(And wait to watch the water clear, I may):

I sha’n’t be gone long.—You come too.

I’m going out to fetch the little calf

That’s standing by the mother. It’s so young,

It totters when she licks it with her tongue.

I sha’n’t be gone long.—You come too.

牧场

我要出去清洁牧场的流泉

我只是停下来把叶子耙开

(也许,我等着看泉水重又清澈)

我不会去很久的---你也来吧。

我要出去牵回可爱的小牛犊

它站在母牛身边,是那样的稚弱

当母牛用舌头去舔它,它竟站立不稳

我不会去很久的---你也来吧。

Mending Wall

Something there is that doesn't love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it

And spills the upper boulder in the sun,

And make gaps even two can pass abreast.

The work of hunters is another thing:

I have come after them and made repair

Where they have left not one stone on a stone,

But they would have the rabbit out of hiding,

To please the yelping dogs. The gaps I mean,

No one has seen them made or heard them made,

But at spring mending-time we find them there,

I let my neighbor know beyond the hill;

And on a day we meet to walk the line

And set the wall between us once again.

We keep the wall between us as we go.

To each the boulders that have fallen to each.

And some are loaves and some so nearly balls

We have to use a spell to make them balance:

"Stay where you are until our backs are turned!"

We wear our fingers rough with handling them.

Oh, just another kind of outdoor game,

One on a side. It comes to little more:

There where it is we do not need the wall:

He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get across

And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.

He only says, "Good fences make good neighbors."

Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder

If I could put a notion in his head:

"Why do they make good neighbors? Isn't it

Where there are cows? But here there are no cows.

Before I built a wall I'd ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offense.

Something there is that doesn't love a wall,

That wants it down." I could say "Elves" to him,

But it's not elves exactly, and I'd rather

He said it for himself. I see him there,

Bringing a stone grasped firmly by the top

In each hand, like an old-stone savage armed.

He moves in darkness as it seems to me,

Not of woods only and the shade of trees.

He will not go behind his father's saying,

And he likes having thought of it so well

He says again, "Good fences make good neighbors."

补墙

有一点什么,它大概是不喜欢墙,

它使得墙脚下的冻地涨得隆起,

大白天的把墙头石块弄得纷纷落:

使得墙裂了缝,二人并肩都走得过。

士绅们行猎时又是另一番糟蹋:

他们要掀开每块石头上的石头,

我总是跟在他们后面去修补,

但是他们要把兔子从隐处赶出来,

讨好那群汪汪叫的狗。我说的墙缝

是怎么生的,谁也没看见,谁也没听见

但是到了春季补墙时,就看见在那里。

我通知了住在山那边的邻居;

有一天我们约会好,巡视地界一番,

在我们两家之间再把墙重新砌起。

我们走的时候,中间隔着一垛墙。

我们走的时候,中间隔着一垛培。

落在各边的石头,由各自去料理。

有些是长块的,有些几乎圆得像球.

需要一点魔术才能把它们放稳当:

“老实呆在那里,等我们转过身再落下!”

我们搬弄石头.把手指都磨粗了。

啊!这不过又是一种户外游戏,

一个人站在一边。此外没有多少用处:

在墙那地方,我们根本不需要墙:

他那边全是松树,我这边是苹果园。

我的苹果树永远也不会踱过去

吃掉他松树下的松球,我对他说。

他只是说:“好篱笆造出好邻家。”

春天在我心里作祟,我在悬想

能不能把一个念头注入他的脑里:

“为什么好篱笆造出好邻家?是否指着

有牛的人家?可是我们此地又没有牛。

我在造墙之前.先要弄个清楚,

圈进来的是什么,圈出去的是什么,

并且我可能开罪的是些什么人家,

有一点什么,它不喜欢墙,

它要推倒它。”我可以对他说这是“鬼”。

但严格说也不是鬼.我想这事还是

由他自己决定吧。我看见他在那里

搬一块石头,两手紧抓着石头的上端,

像一个旧石器时代的武装的野蛮人。

我觉得他是在黑暗中摸索,

这黑暗不仅是来自深林与树荫。

他不肯探究他父亲传给他的格言

他想到这句格言,便如此的喜欢,

于是再说一遍,“好篱笆造出好邻家”。

译者:梁实秋

The following are characteristics of Modernism:

1.Marked by a strong and intentional break with tradition. This break includes a strong reaction against established religious, political, and social views.

2.Belief that the world is created in the act of perceiving it; that is, the world is what we say it is.

3.There is no such thing as absolute truth. All things are relative.

4.No connection with history or institutions. Their experience is that of alienation, loss, and despair.

5.Championship of the individual and celebration of inner strength.

6.Life is unordered.

7.Concerned with the sub-conscious.

Modernist literature

Modernist literature is sub-genre of Modernism, a predominantly European movement beginning in the early 20th century that was characterized by a self-conscious break with traditional aesthetic forms. Representing the radical shift in cultural sensibilities surrounding World War I, modernist literature struggled with the new realm of subject matter brought about by an increasingly industrialized and globalized world.

In its earliest incarnations, modernism fostered a utopian spirit, stimulated by innovations happening in the fields of anthropology, psychology, philosophy, political theory, and psychoanalysis. Writers such as Ezra Pound and other poets of the Imagist movement characterized this exuberant spirit, rejecting the sentiment and discursiveness typical of Romanticism and Victorian literature for poetry that instead favored precision of imagery and clear, sharp language.

This new idealism ended, however, with the outbreak of war, when writers began to generate more cynical postwar works that reflected a prevailing sense of disillusionment and fragmented thought. Many modernist writers shared a mistrust of institutions of power such as government and religion, and rejected the notion of absolute truths. Like T.S. Eliot's masterpiece, The Waste Land, later modernist works were increasingly self-aware, introspective, and often embraced the unconscious fears of a darker humanity.[1]

Characteristics of Modernity/Modernism

Formal/Stylistic characteristics

Juxtaposition, irony, comparisons, and satire are elements found in modernist writing. The most obvious stylistic tool of the modernist writer is that it is often written in first person. Rather than a traditional story having a beginning, middle and end, modernist writing typically reads as a long stream of consciousness similar to a rant. This can leave the reader slightly confused as to what they are supposed to take away from the work. Juxtaposition could be used for example in a way to represent something that would be oftentimes unseen, for example, a cat and a mouse as best friends. Irony and satire are important tools for the modernist writer in aiding them to make fun of and point out faults in what they are writing about, normally problems within their society, whether it is governmental, political, or social ideas.

Thematic characteristics

For the first-time reader, modernist writing can seem frustrating to understand because of the fragmentation and lack of conciseness of the writing. The plot, characters and themes of the text are not always linear. The goal of modernist literature is not heavily focused on catering to one particular audience in a formal way. Modernist writing is more interested in getting the writer's ideas, opinions, and thoughts out into the public at as high a volume as possible. Modernist literature often forcefully opposes or gives an opinion on a social concept. The breaking down of social norms, rejection of standard social ideas and traditional thoughts and expectations, objection to religion and anger towards the effects of the world wars, and the rejection of the truth are topics widely seen in this literary era. A rejection of history, social systems, and a sense of loneliness are also common themes. In the interest of elitist exclusivity, past modernist writers have also been known to create their text in a stylistic and artistic way, using different fonts, sizes, symbols and colors in the production of their writing.

Modernist Writers

Modernist Writers

- Sherwood Anderson

- Djuna Barnes

- Samuel Beckett

- Andrei Bely

- Gottfried Benn

- Menno ter Braak

- Mikhail Bulgakov

- Morley Callaghan

- Ivan Cankar

- Joseph Conrad

- Hart Crane

- e. e. cummings

- John Dos Passos

- T. S. Eliot

- William Faulkner

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Robert Frost

- E. M. Forster

- Carlo Emilio Gadda

- Knut Hamsun

- H.D. (Hilda Doolittle)

- Jaroslav Haš�������ek

- Ernest Hemingway

- James Joyce

- Franz Kafka

- D. H. Lawrence

- Wyndham Lewis

- Mina Loy

- Hugh MacDiarmid

- Katherine Mansfield

- Robert Musil

- Aldo Palazzeschi

- Boris Pasternak

- Luigi Pirandello

- Katherine Anne Porter

- Ezra Pound

- John Cowper Powys

- Marcel Proust

- Italo Svevo

- Dorothy Richardson

- Rainer Maria Rilke

- Gertrude Stein

- John Steinbeck

- Wallace Stevens

- Dylan Thomas

- Jean Toomer

- Federigo Tozzi

- Nathanael West

- William Carlos Williams

- Virginia Woolf

- W. B. Yeats

American Modernism

Writers, Known as "The Lost Generation" American writers of the 1920s, brought Modernism to the United States. For writers like Hemingway and Fitzgerald, World War I destroyed the illusion that acting virtuously brought about good. Like their British contemporaries, American Modernists rejected traditional institutions and forms. American Modernists include:

Ernest Hemingway - The Sun Also Rises chronicles the meaningless lives of the Lost Generation. Farewell to Arms narrates the tale of an ambulance driver searching for meaning in WWI.

F. Scott Fitzgerald - The Great Gatsby shows through its protagonist, Jay Gatsby, the corruption of the American Dream.

John Dos Passos, Hart Crane, and Sherwood Anderson are other prominent writers of the period.

海明威与菲茨杰拉德:美国文学史上最让人唏嘘的友情

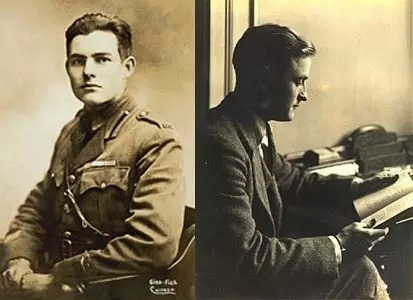

年轻的海明威和菲茨杰拉德,美国文学史上最好的,也是最让人唏嘘的友情,正如他们的才华一样:顶点如此辉煌,结束悄无声息。

在1925年四月下旬的巴黎,年轻充满活力但穷困的海明威在位于Montparnasse区的以讲英语为主的Dingo Bar里遇上了同样年轻(只比他大三岁),但是从名校普林斯顿(Princeton)出身(尽管没能够毕业),已经在《周六晚邮报》拥有数百万读者的菲茨杰拉德。当时正好是菲茨杰拉德的最杰出的一部作品《了不起的盖茨比》(The Great Gatsby)出版后两个星期,正可谓是青年才俊意气风发。而海明威虽然当时已经走上写作之路,但不曾出版任何作品,只是写了尚未为人知一些短故事和小诗。两人当时境况明显悬殊很大。

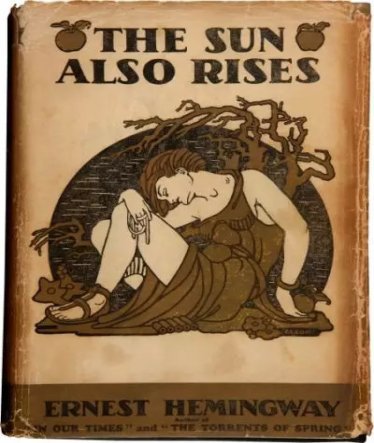

海明威第一部作品《太阳照常升起》的封面。

菲茨杰拉德在他们的第一次会面后,就向他的编辑推荐海明威是个人物(“the real thing”),并帮助他介绍认识了出版商Scribner's。次年,海明威的第一部作品《太阳照常升起》(The Sun Also Rises)就由Scribner's出版,从此成为了世界著名的作家。可以毫不夸张的说是菲茨杰拉德发掘了海明威,并给了他一个巨大的怎么说都不为过的推动和帮助。 菲茨杰拉德的巨大影响力和在文学上的指点,对于海明威以后的成功贡献十分重要。可以说,在20年代剩下的五年中,菲茨杰拉德对于建议和修改海明威的作品比在他本人的作品上的投入还要多。给世人的感觉是,自从海明威开始能够出版后,菲茨杰拉德对他自己写作的成功或者失败已经不在乎了。

海明威年轻时

而对于菲茨杰拉德来说,海明威在他一生中既是文学上的竞争对手又是理想中的英雄化身的综合体。海明威充满阳刚的形象,运动员的体魄,善饮酒的作风和曾经参加过战斗的经验,这些都是菲茨杰拉德一直向往但不曾具有的。他们二人拥有相似的家庭背景但却是迥然不同的风格。首先,他们都是在美国中西部长大,菲茨杰拉德来自于明尼苏达的圣保罗,而海明威出生在芝加哥郊区。他们的家庭均是有一个羸弱的父亲和一个强势的母亲。菲茨杰拉德还在母亲肚子里的时候他的两个姐姐就相继夭折;海明威虽然有不少姐姐,但是他一直期盼能有一个弟弟,最终他的弟弟诞生的时候他则已经完全长大成人了,对于他想要的“兄-弟”关系已经太晚了。所以菲茨杰拉德对于英雄的成瘾与海明威一直想要成为一个英雄,他们的分量一样沉重。这真是一个绝妙的搭配:菲茨杰拉德需要一个英雄的形象来崇拜,而海明威则完全符合这一点。

“蜜月期”的海明威和菲茨杰拉德

菲茨杰拉德和海明威从此进入了“蜜月期”。他们交友至深,甚至相互昵称“菲兹”与“海姆”。泽尔达·菲茨杰拉德(菲茨杰拉德的妻子)嫉妒的说:“我丈夫和海明威他们两个人!哼,他们俩在一起的样子简直就像是一对情侣!”在《流动的盛宴》中,海明威记录了这样一个细节,菲茨杰拉德请他吃饭。“要向他的朋友请教一件无比重要的事情。”海明威应允了,原来菲茨杰拉德听泽尔达抱怨他有“尺寸问题”,不可能获得任何一个女人的欢心。海明威把菲茨杰拉德叫进厕所,观察之后,安慰菲茨杰拉德“仅仅是角度问题,你从上面往下看自己,就显得缩短了。”为了证明自己说的话可靠,海明威还建议菲茨杰拉德跟自己一起去卢浮宫,看希腊的裸体雕像。

在《太阳照常升起》出版之后,海明威与他第一任妻子离婚,迎娶了来自阿肯色州的家境富有的交际花波琳Pauline。住在Pauline的叔叔送给他们的在弗罗里达州Key West的海边别墅里,海明威写出了开始为他带来荣誉和声名的《永别了,武器》A Farewell To Arms,成为了文学界的新星。

与海明威的蒸蒸日上相反,自从遇上海明威后,菲茨杰拉德的写作生涯可谓是一头撞上了墙。不论出于何种原因(海明威的分析是,《伟大的盖茨比》的巨大成功和评论家的褒奖,让菲茨杰拉德陷入了唯恐达不到同样高度的瘫痪状态),菲茨杰拉德没有能够完成任何一部长篇作品,直到九年后才出版了《夜色温柔》Tender Is The Night,而不论是在商业上还是在评论家眼里它都是一部平庸之作。1925年后,菲茨杰拉德的生活更像是陷入了一种三重的挣扎:他在酒精中的沦陷,更加失控的妻子(泽尔达在30年代后因为精神状况多次入院治疗),和他想要写长篇但是迫于奢侈生活不得不放弃的矛盾。此后,在大萧条的年代,他再也不能从杂志商那里拿来金钱的时候,他不得不到好莱坞去写一些从未被拍成电影的剧本,来勉强维持他的温饱生活,来支付泽尔达的住院费,和供他女儿念完高中。海明威有理由瞧不起菲茨杰拉德为杂志的撰稿,更加不用为生活所迫去好莱坞写剧本。此外,还有其他的一些原因也让两人友谊出现裂痕:菲茨杰拉德实际上对酒精的耐受程度很低,这在海明威眼中是一个男人最不可接受的一点。另外的一个事实是,海明威与泽尔达相互鄙视。泽尔达称海明威“如橡皮支票一样的虚伪”,海明威则多次指责泽尔达鼓励菲茨杰拉德酗酒耽误了他的写作才华。

菲茨杰拉德和妻子泽尔达,泽尔达是《了不起的盖茨比》中女主角黛西的原型:美丽,高傲,富有才华却又拜金,物质,她引导菲茨杰拉德挥金如土,最终使他荣光不再。

重重压力之下,菲茨杰拉德出版了他著名的一系列散文,最后被汇集成书为《崩溃》The Crack-Up,主要讲述了他自己本人从巅峰后的失败以及原因。海明威对于这种向公众的坦白感到很吃惊,他认为这不是男人做的事情,应该自己单独处理自己的问题,而不是把它散布给大众,然后博取同情。不久,海明威在他的著名短篇《乞里马扎罗的雪》Snows Of Kilimanjaro中,直接描写了一个失败的作家菲茨杰拉德,关于他的“对于财富的浪漫的敬畏”以及这种敬畏,作为原因之一是怎样毁了他的一生。感到深深地受到了伤害,菲茨杰拉德读后给海明威和他们共同的编辑(就是最初介绍海明威认识的那位,太具有讽刺意义了)发去了抗议信,于是此后的版本中,菲茨杰拉德的名字被替换成了Julian,但是了解背景的人们一看就能明白这里引用的是谁。事实上,《乞里马扎罗的雪》与《崩溃》的故事大纲并没有太大差别,都是描写一个失败的作家面对各自失败的生涯,只不过一个是虚构的背景,一个则是更适合作为今天电视谈话节目的谈资。更令菲茨杰拉德伤心不已的是,当他最终好不容易出版了《夜色温柔》后,他诚恳邀请海明威的评论,却是不屑一顾(虽然几年之后,海明威重读了此书并给予了正面的评价)。

菲茨杰拉德一家

1935年12月,菲茨杰拉德处于人生低谷,他写信向海明威倾诉,海明威的建议是:他可以安排人在古巴把菲茨杰拉德杀了,这样泽尔达和小司科特就可以拿到保险金了。海明威在回信中如是说:“我会写一篇优美的讣告,马尔康·考雷会为新共和国从中剪出最好的部分,而我们可以取出你的肝脏捐给普林斯顿博物馆,心捐给广场酒店,一只肺捐给麦克斯·佩金斯,另一只给乔治·贺拉斯·罗利摩。如果还能找到你的睾丸,我会通过巴黎大区将它们带去巴黎,带到南方的安提比斯,从‘伊甸岩’上将它抛入海中,我们还会叫麦克利什写一首神秘主义诗歌,在你就读的天主教学校(纽曼?)朗诵。或者你希望我现在就来写那首神秘诗?我们来瞧瞧。

(阿尔卑斯山沿海的安提比斯)

于是,从这些灰色山庄中

他烂醉如泥,没缠兜裆布

纵身

跃下?

不。

那是某个侍者?

是。

哦,温柔地推动绿色草尖

不要搔弄我们的菲茨的鼻孔

越过

波动的、未被本·芬尼研究过的灰色大海中

比我们欠艾略特的债更深的深处

它们嘭嘭抛下他的两个,最后是他的一个

圆形的、胶质的、布满缝隙的……

它们上升,旋即消失

在自然的

非人工的

恐惧中

下沉时没有激起涟漪。”

《司科特·菲茨杰拉德的睾丸

从伊甸岩被抛入海中而朗诵的诗》

1936年,菲茨杰拉德不幸染上肺病,妻子又一病不起,使他几乎无法创作,精神濒于崩溃,终日酗酒。在最后的日子里,他落魄潦倒,无人问津。而海明威却成为然而三十年后,海明威的最后岁月,困扰他的却正和他此前指责菲茨杰拉德一样:酒精,精神疾病,和悄悄逝去的自我价值,他终于理解了菲茨杰拉德,海明威在他自杀前写的最后一部作品《流动的盛宴》中,关于菲茨杰拉德的那一章,扉页上有这么一段话:

“他的才华是那么的自然,就如同蝴蝶翅膀上的颗粒排列的格局一样。最初,他并不比蝴蝶了解自己的翅膀那样更多的注意到自己的才华,他也不知道自从何时这些被洗刷掉和破坏。直到后来,他开始注意到了他破损了的翅膀和翅膀的结构,他开始明白不可能再次起飞了,因为对于飞行的热爱已经消逝,他唯一能够回忆起的是,当初在天空中的翱翔是多么的轻而易举啊。”

Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was named after the anthology The New Negro, edited by Alain Locke in 1925. Centered in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City, the movement impacted urban centers throughout the United States. Across the cultural spectrum (literature, drama, music, visual art, dance) and also in the realm of social thought (sociology, historiography, philosophy), artists and intellectuals found new ways to explore the historical experiences of black America and the contemporary experiences of black life in the urban North. Challenging white paternalism and racism, African-American artists and intellectuals rejected merely imitating the styles of Europeans and white Americans and instead celebrated black dignity and creativity. Asserting their freedom to express themselves on their own terms as artists and intellectuals, they explored their identities as black Americans, celebrating the black culture that had emerged out of slavery and their cultural ties to Africa.

The Harlem Renaissance had a profound impact not only on African-American culture but also on the cultures of the African diaspora as a whole. Afro-Caribbean artists and intellectuals from the British West Indies were part of the movement. Moreover, many French-speaking black writers from African and Caribbean colonies who lived in Paris were also influenced by the Harlem Renaissance.

Historians disagree as to when the Harlem Renaissance began and ended. It is unofficially recognized to have spanned from about 1919 until the early or mid 1930s, although its ideas lived on much longer. The zenith of this "flowering of Negro literature", as James Weldon Johnson preferred to call the Harlem Renaissance, is placed between 1924 (the year that Opportunity magazine hosted a party for black writers where many white publishers were in attendance) and 1929 (the year of the stock market crash and then resulting Great Depression).